An adventure for PCs based in London, possibly working for the Phantasmological Society.

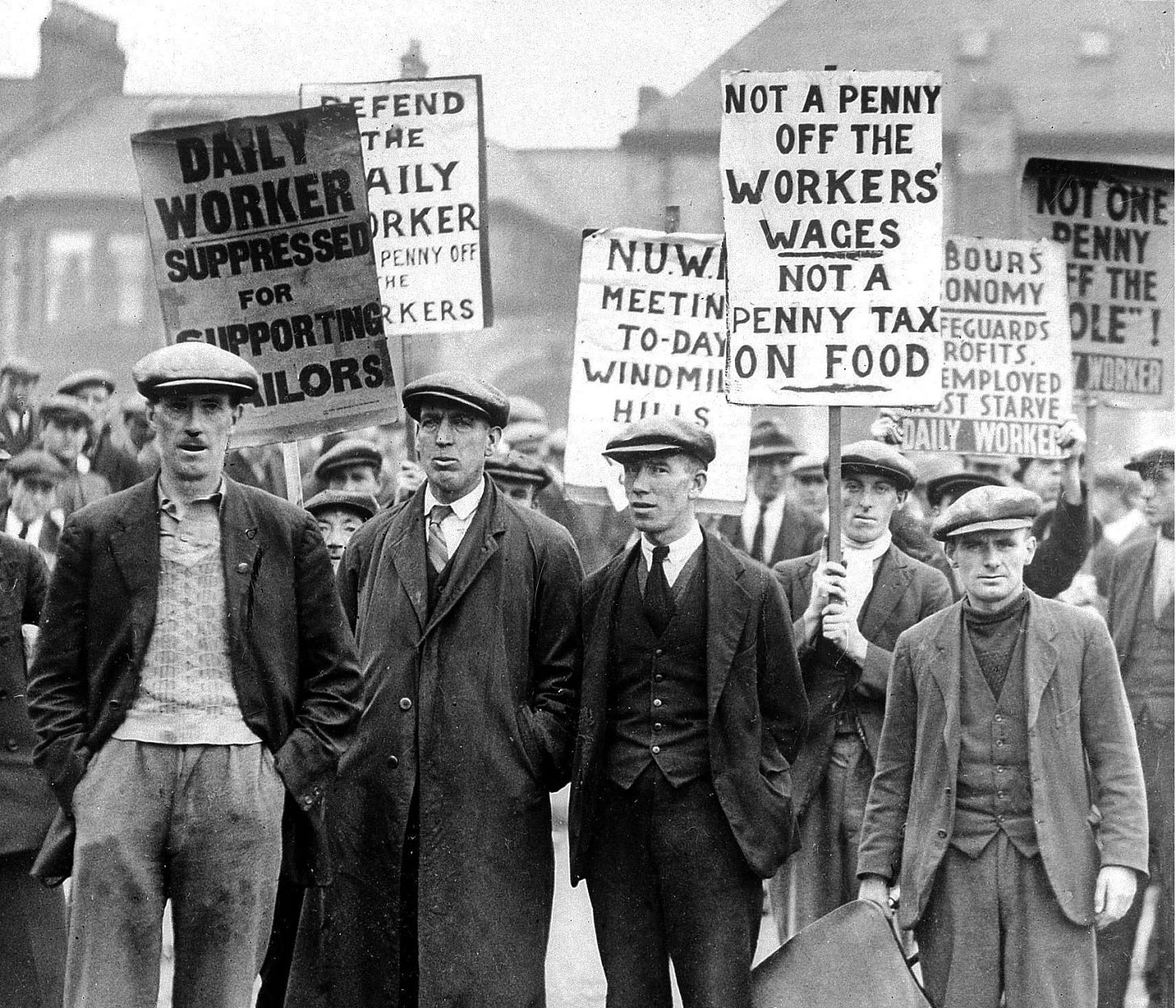

STRIKE!

May Day in Birmingham. The railwaymen, the printers and the steelworkers have come out in support of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain. Trams and newspapers shut down.

Oswald Mosley, at this stage a good Fabian, speaks to the crowd in Victoria Square on the evils of capitalism and all the great things he’ll do for the common man if he’s elected to Parliament in the upcoming Smethwick by-election. Red rosettes and flags.

Dapper young men in tailored suits and flat caps flood the square. Brass knuckles and steel-capped boots. Rubberised batons tipped with electrodes that paralyse anyone they hit. Gas bombs. One guy has something like a portable Tesla coil that zaps communists with purple lightning.

“This rally is shut down - by order of the Peaky fooking Blinders!” You don’t have to say that last part but you can if you want.

Frank Cassidy of the Trades Council (head of the Typographical Association) has asked you to look into where the hell the Blinders are getting this stuff.

A gruff, square-headed man with a bristly moustache, a bit slow on the uptake but sincerely concerned for the well-being of the working class. Thinks correctly that Mosley is a wrong ‘un but backing him in the election against the Tories.

M. J. Pike. Tory candidate for Smethwick. A round-faced nonentity with a habit of trailing off halfway through sentences. His main line of attack is that Mosley is too rich. Nobody seems to know his full first name.

Neville Chamberlain, MP for Birmingham-Ladywood. Coordinating resistance to the strike - getting scabs to run the buses, importing the British Gazette to tell the government’s side of the story. Helped forge the Zinoviev letter. Mosley was 77 votes short of claiming his seat in ‘24.

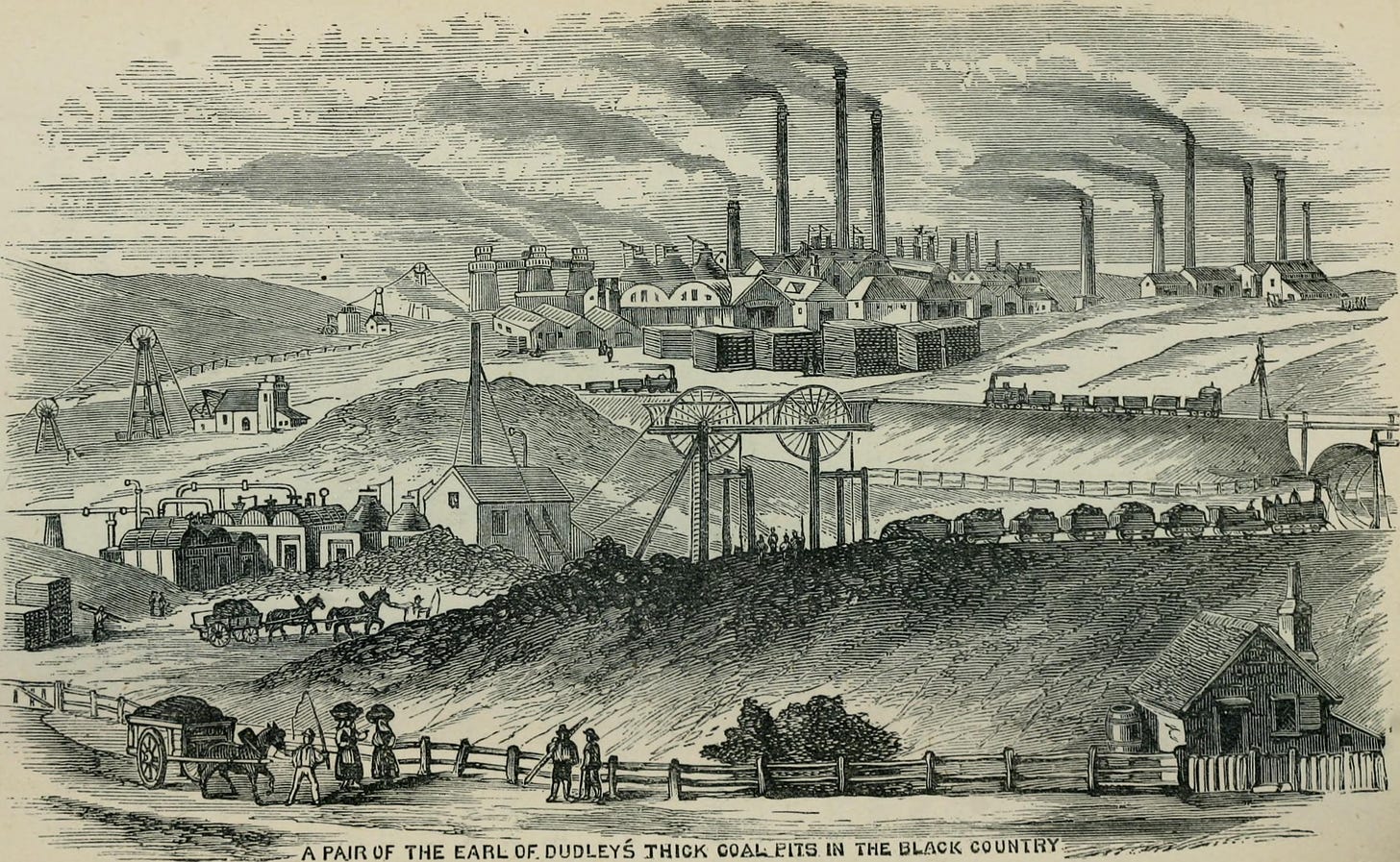

William Humble, 3rd Earl of Dudley. Major donor to the Tories. Inherited a dozen Black Country industrial concerns. Backing Pike. You can trace the Blinders’ science-fiction weaponry to his factories in Tipton, where greasy girls in overalls piece atomic batteries together.

He lives at Witley Court, in the countryside, but spends much of his time overseeing his collieries and steel mills. He’s gotten more into it lately. He’s very involved in the election and thinks that Socialism and Homosexuality are together going to be the death of the world.

Romantically fixated on Venetia Stanley, a key figure in the London witch-cult, who sacrificed her husband Edwin Montagu to the Devil. He’s the father to Venetia’s daughter Judith, who they conceived in the passionate throes of a Black Mass.

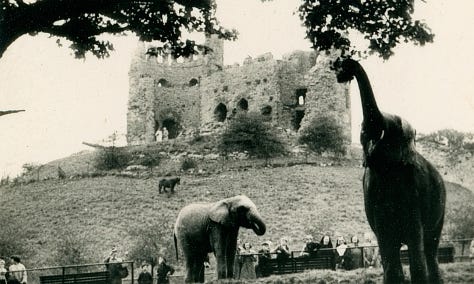

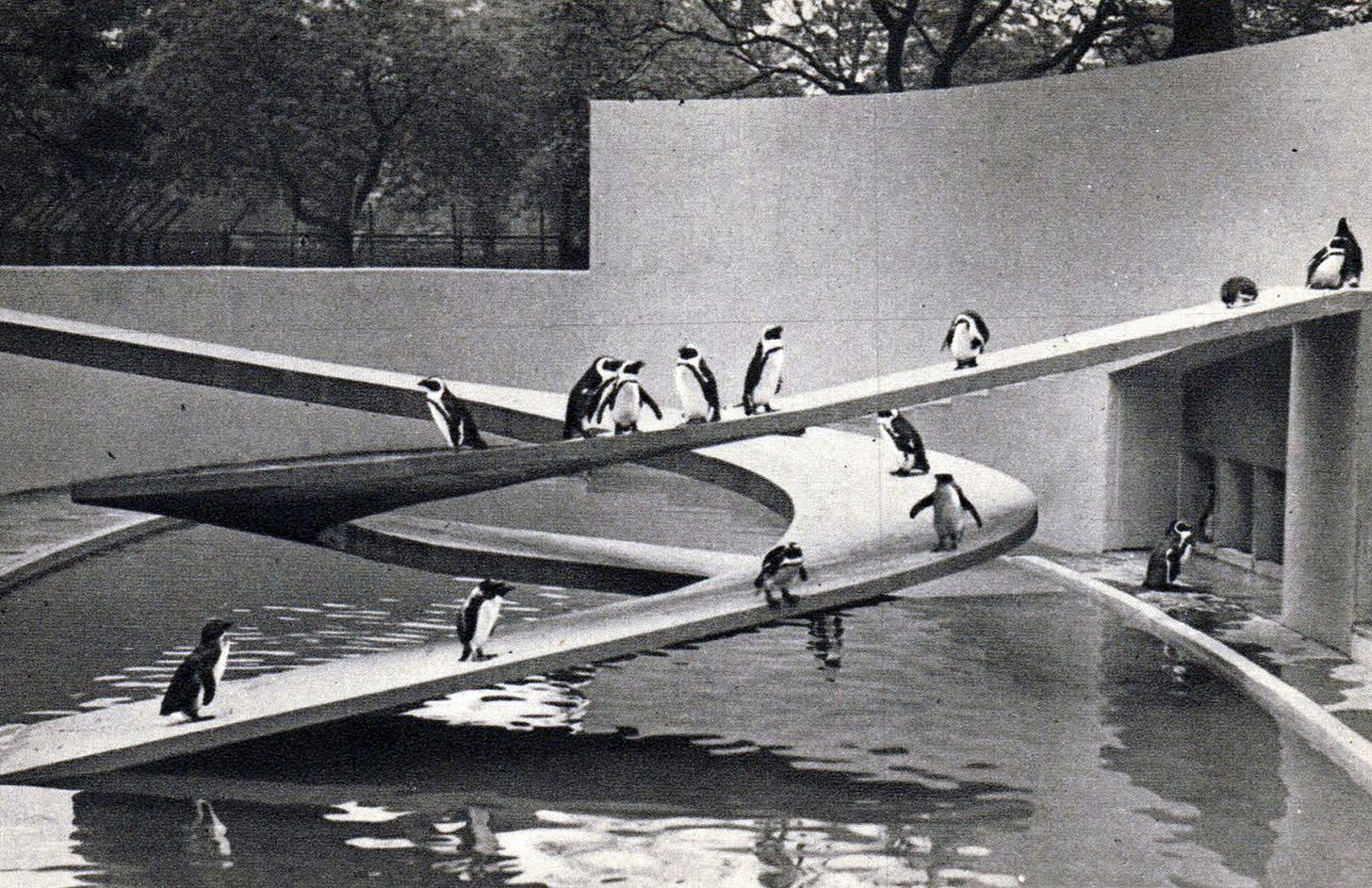

Owns Dudley Castle and the surrounding Castle Hill. It’s said to be one of the most haunted castles in England, with a grey lady and a drummer boy from the Civil War. Has employed an esoteric architect, Berthold Lubetkin, who got out of Tbilisi one step ahead of the Bolsheviks, to build a Constructivist zoo on the property.

The Dudley Canal runs under Castle Hill, an underground dock and network of flooded tunnels connecting with the abandoned limestone quarry and natural caverns. The shafts from the Coneygree Colliery (where the Black Country Living Museum is now) break through into the caverns. Of course Humble owns the pit.

The castle grounds are full of hidden doors. A stone coffin in the chapel that opens to reveal stairs leading down, and a trapdoor at the back of the polar bear exhibit. You don’t like the way the penguins look at you. Do they have teeth?

Half a billion years ago, Earth was psychically invaded by cheerful bodiless creatures known as the Great Race of Yith, who took over the bodies of a species of ten-foot-long hallucigenian worms, and set about establishing a highly advanced technological civilisation on the humid shores of the Panthalassan Ocean.

The Yithians aspired to know all facts, ever, in the universe. To this end, they developed the ability to swap minds with creatures from the distant future, sending their mental explorers ahead to chart the voids of time.

The databanks and time tombs of their library city of Pnakotus, now buried beneath the sands of Australia’s Great Sandy Desert, contain complete maps of all of history, including hard proof of casual determinism, and juicy details of the universe’s end.

The Yithians had criminals. And cultists. One in particular, Krrk’atak, a worshipper of the Devourer, a beast of cosmic darkness which came into existence one second after the Big Bang and despises anything younger than itself.

Krrk’atak was a genius. The Stalin and Moriarty of his day. Loved and feared in equal measure. Finally he was caught by the Yithian authorities and sentenced to death by atomic disintegration.

Then he revealed his backup plan. He’d already created a psychic link with a Yithian temporal relay, something like a milky crystal pyramid with a wad of coiled larvae trapped inside. This relay was buried by his servitors in a peat swamp, which became coal.

Three hundred million years passed.

Jack Marsh, miner, sixteen years old, short and spotty and not particularly bright, is naked on all fours, chipping away at a coal face underneath Tipton. Something smooth, with regular edges, comes off in his hand. He holds it up to the lantern, wondering what it is.

His mind is whisked away to the Carboniferous. He gets a brief impression of conical figures, and wonders what happened to his feet. Then his mind is vaporised, along with Krrk’atak’s body, as the death sentence is carried out.

Krrk’atak stands up, in Marsh’s body. Weirdly small, and he’s not sure about these “hand” things, but it’ll do.

He knows that coal is an important transitional fuel, and that he is most likely in the critical hundred-year seed stage of an early industrial civilisation. Exactly as planned. He determines that the mode of production is capitalist and goes to find the guy who owns the mine.

He supplies Lord Humble with the secrets of Yithian technology, in exchange for access to resources. Humble sets up factories to build the things he needs. When the miners go on strike, Humble brings the Blinders in and gives them the tools they need to break it.

He’s building a gateway to the past.

Get a job in one of Humble’s factories. His workers are well treated. Each overseer wears a medallion round his neck. A trilobite. Iridescent black. It looks dead but if you watch it long enough you can see it wiggle.

The workers assemble strange devices from machinery you don’t understand. Other factory owners have expressed interest in understanding the process but Humble maintains total secrecy. Marsh is on hand as “engineering consultant”, to the bafflement of his mates, who always thought he was pretty thick.

The machines are shipped via the Dudley Canal to the underground dock below Castle Hill.

The caverns crawl with parasitic trilobites. Known as Dudley locusts. Marsh/Krrk’atak has shown Humble how to resurrect them from fossils. They cling to the throats of workers and drink their agency, making them obedient and numb. Underground dormitories so no-one has to leave.

The time gate in the vast central cavern will open a door to one second after the Big Bang and summon an aspect of the Devourer through. Tests have been done and temporal disturbances created. Hence the ghosts of Dudley Hill, visions from the past and strange blue mists creeping across the lawn at night.

The tectons in the zoo, brutalist concrete spirals and enclosures, are designed to reshape Minkowski space. The animals are possessed by the Devourer. The penguins have teeth, the gorillas round leechlike mouths in their palms, the elephants hungry trunks.

As you explore the Black Country you might see the aurora flickering over Castle Hill, or renegade trilobites lurking in the canals. Escaped predator penguins. Blinders with zap guns beating up strikers and shaking down newsagents for protection money.

You’ll also see strangers. Randoms. People who don’t fit in. Like Marsh they speak with a high fluting accent, unlike anything from Earth. Most of them are white, or Aboriginal Australian. They ask obvious questions and violate simple social codes, though not to the point of being locked up.

These are the Yithian time police.

It took them long enough. But they worked out that Krrk’atak escaped. And they’re going to kill him again.

(Why don’t they find the relay and destroy it? Casual determinism. It’s already happened from their perspective so they can’t. Also they don’t all know literally everything that’s going to happen - the knowledge is reserved for scholars as it causes you to become insane.)

My apologies to Patrick Stuart for using trilobites for evil.

More games should involve elections. Huge potential. A good election has a million little subplots, securing key endorsements, canvassing voters, even sabotaging the ballot if you don’t like the way it’s turning out. This one could use a random encounter table.

Since I couldn’t work it in before, here’s Samuel Sidney’s description of the Black Country:

“The pleasant green of pastures is almost unknown, the streams, in which no fishes swim, are black and unwholesome; the natural dead flat is often broken by high hills of cinders and spoil from the mines; the few trees are stunted and blasted; no birds are to be seen, except a few smoky sparrows; and for miles on miles a black waste spreads around, where furnaces continually smoke, steam engines thud and hiss, and long chains clank, while blind gin horses walk their doleful round. From time to time you pass a cluster of deserted roofless cottages of dingiest brick, half swallowed up in sinking pits or inclining to every point of the compass, while the timbers point up like the ribs of a half decayed corpse.”

History of the ‘26 General Strike and Mosley’s run against Chamberlain. It’s okay to play a little loose with the timing though - I figure Strange Aeons plays out in an alternative universe where all the cool stuff happened at the same time.

Photos of the Seven Sisters limestone caverns, and of the Dudley Zoo, in 3D for some reason. And the Tipton Civic Society’s historical shots of the Black Country. Thanks again to local historians - your work is never done.

Man, that description of a landscape transformed/ruined by 'progress' reminds me of two things:

1. What I've been told the Ruhrgebiet here in Germany was like until the 70s - where the sky was yellow from the industrial fumes.

2. I was travelling in China by train in 2007 and we were approaching Lanzhou. From the train window it looked like everything, roofs, sidewalks and all, was covered in half a meter of white, sparkling snow. Which was impossible as it was a hot summer. It was something raining down from the factories, ignored by the people unless they had to shovel it out of the way...