An alchemist’s shop in the Old City of Shanghai.

The labyrinth of streets east of the Yuyuan Garden. Near the City God Temple, home to Shanghai’s tutelary deities. Unemployed men sleep in the gutters. Rickshaw drivers and workers from the Japanese-owned cotton mills linger outside cinemas and restaurants, smoking, watching the crowds.

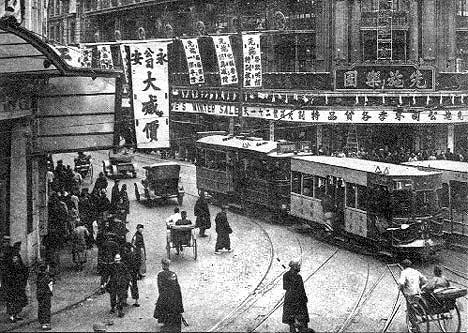

Streetcars rattle down the wider roads. Wheelbarrows laden with baskets of live turtles and bundles of sugarcane - pairs of men barking at each other as they pull gigantic loads. Bridges across filthy canals. Decrepit tea-houses by slimy green pools.

Transactions everywhere you look - cobblers begging for business from courtesans with bound feet. Fruit markets. Money-changers. Sikh policemen. Americans on horseback. Ducks hanging in butchers’ windows. Women in cheongsams. Men in padded jackets and Western-style hats.

Banners fly from upper stories - overhanging alleys. Cigarette ads. Art Deco posters for Pond’s Vanishing Cream. Communist slogans stuck to walls. Lepers with begging bowls. Wet markets - streets of birdcages, flowers, fish.

Offal simmering in pans. Naked White Russian dancers in mirrored cabarets. Washing lines strung across alleys. Dance-hall girls waiting for soldiers to buy their tickets - hoping for an Englishman to carry them away.

Warehouses by the Huangpu loaded with Malayan rubber, Siamese sandalwood, Filipino teak. Junks and sampans crammed with peanuts and scrap iron. Dangerously low in the water.

Sweaty waistcoated bankers check their pocket watches. Skinny men with bamboo trolleys haul wool-carding machines, pigs, furniture, old women, sacks of pepper, grand pianos, guns, strongboxes full of gold.

Sailors of all nations go in search of entertainment. Expensive machines demand emergency repairs. Cranes slump into the mud. Anti-foreign riots break out and are suppressed.

Marxist agitators hand out copies of New Youth magazine. Shaven-headed Green Gang touts lure tourists into gambling dens and brothels. Puppets box and wrestle. Toffee-brown lumps of opium take away the pain of starvation and work.

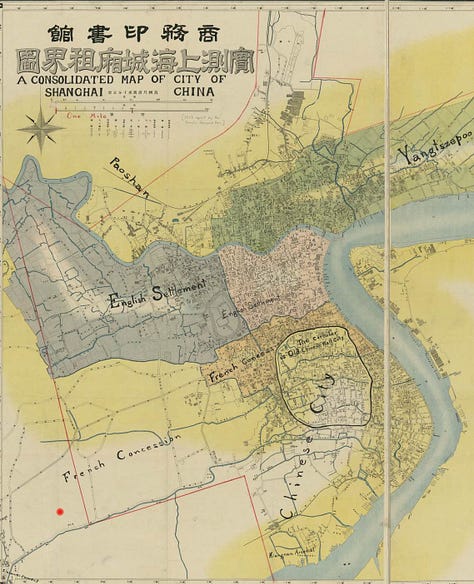

Nobody really runs the city - one quadrant is French, one Anglo-American. Each nation has its own courts. China as a whole is divided between warlords after the Qing collapse. The Kuomintang, you hear, are marching north from Guangzhou to unite the country and bring all the petty kings to heel.

You have no idea how it will turn out.

Uncle Ho’s shop is an oasis of calm among the bustling streets.

He’ll offer you tea. Assess the state of your meridians with a glance, perhaps a light touch on the wrist, and determine the exact variety you require. You’ll like the taste.

A lacquered cabinet behind the counter.

Dozens of small labelled drawers. Each holding a different herb. Ho knows them all by memory and can discourse for hours on the medicinal powers they possess.

He’s petitioned for assistance with all manner of maladies. Infertility. Flatulence. Gout. Ingrown toenails. Hair loss. Ringworm. Vertigo. Deafness. Congenital idiocy. Brain cancer. Kidney stones.

Selective about his customers. Won’t guarantee results. Overcharges the rich. Gives freely to the City God Temple and to the urban poor.

Westerners rarely visit the Old City.

But a few will find their way to Ho’s shop. Sit and talk for hours over steaming cups of tea at the octagonal stone table in the pocket-sized garden behind his house. One lantern. One tree. Shielded from street noise by the courtyard’s wooden walls.

A single fat carp lives in his tiny pond - it’s rarely seen.

His shop smells like nothing you’ve ever encountered.

Sulphur. Cinnabar. Rhino horn. Tiger penis. Crushed malachite. Lapis lazuli.

Six colours of lingzhi mushroom on a damp log in the basement, where he keeps a private fungus farm. Turkestan salt. Arsenic. Fingernail-sized black pearls. Iridescent beetles. The juice of a mellified man, preserved in honey for a hundred years, capable (it’s said) of setting fractured bones.

Bear bile, humanely harvested, since Uncle Ho has sworn a great oath never to cause needless suffering to a living being. Pangolin scales. Dried human placenta. Hornets’ nests. Live seahorses and scorpions. Mummified snakes. Toads preserved in wine. A jar labelled “stone bell milk” containing liquefied stalactite.

Incense clocks whose scent subtly changes with the hours. Phoenix-brain polypore. Five Minerals Powder. Six-And-One Mud. Camphor oil. Powdered bark. Salamander liver. Red clay. Deer-antler glue. Wasps preserved in amber. Tubes of dried mugwort. Fossilised mastodon teeth. Crocodile skin.

The classic texts of Chinese alchemy.

Discourses on Salt and Iron. The Solemn Philosopher. Sitting In Oblivion. A recipe for the Lunar Efflorescence of the Yellow Solution, which makes you change forms ten thousand times and float off to the Palace of Purple Tenuity with eyes like luminous moons. Gold needles for eye surgery, kept lethally sharp.

The shop seems small at first. But there’s another door. And another. Does he own this whole block? How far down does it go? How many basements? In which set of rooms does he actually live?

Uncle Ho wants to live forever.

Some say he’s one of the Eight Immortals. Or the alchemist Xu Fu, who sailed west 2000 years ago to seek the elixir of life. Immortality stolen from him by an evil sorcerer - perhaps the notorious criminal mastermind Wu Fang - and he wants it back. Ho chuckles merrily and changes the subject when asked.

His researches are endless.

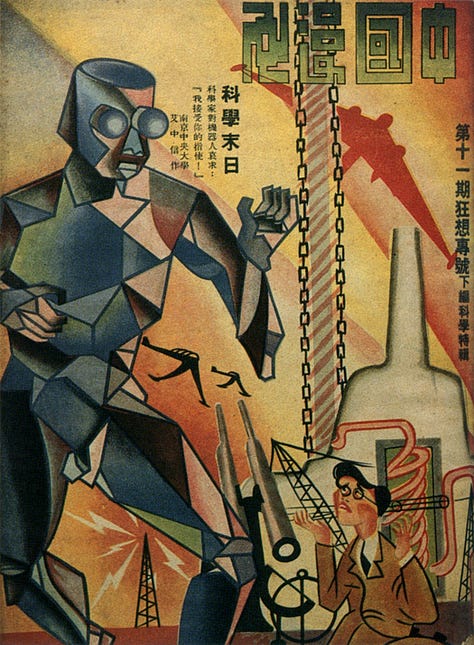

Keeps up to date with modern science. Corresponds with doctors in London and Baltimore. Schools of tropical medicine in Singapore and New Orleans. Missionaries all around the world.

Has definitively proved that the element of mercury is a deadly poison with zero restorative properties. Keeps coming back to it. Still secretly thinks there’s a way to use it as the basis for an elixir of life.

Wants to create the Pill of Immortality. Believes it can be done.

In constant need of obscure reagents, strange chemicals, occult devices from all corners of the globe. Getting old. Can’t do everything himself. People know he can be trusted, a rare thing in China - they come to him for help.

He needs assistants. That’s where you come in.

Uncle Ho has enemies.

The Green Gang don’t like him. The Western powers suspect him of anti-foreign sentiment. The Communists want to eliminate old-fashioned superstition.

Rival wizards are constantly dispatching their esoteric servitors to grab all his secrets and rip out his soul. He’s under perpetual magical attack.

Fills his shop with anti-magic wards. Rarely leaves.

Paper fulu talismans stuck above the door. Soldiers painted on the walls. Coin strings dangling from the ceiling. Lions carved from peachwood holding octagonal mirrors. Demons see their own hideous faces - recoil in horror, flee.

Wu Fang, the most dangerous man alive, would like him dead. Or so it’s said.

Keeps to hand Little Qin, a hand-sized box turtle with the character for “warrior” inscribed on its shell. Deploys it as a chess clock - it marches across the table when he’s playing go with guests.

Rumour suggests that Qin is the keystone of Ho’s spiritual defences. If someone killed the turtle, Wu Feng would slay Ho instantly and subjugate the globe.

Ho cheerfully denies this. He is just a humble old man with an eccentric hobby. People invent the most ridiculous stories about him. Would you like more tea?

More flavour: Streets are always wet and slick. Crippled beggars congregate on streets near temples. Police would probably beat lepers or anything looking contagious, though. The canals stink to heaven. Sounds of 黃色歌曲 yellow music leaks from the doors and windows of the dance halls. Uncles clustered around tables watching 象棋 elephant chess players and shouting advice. Barkers with signs. Mid-day is more quiet as people avoid the heat. Mornings and especially evenings are busiest.